May 22, 2019

Using OO in Business Applications

The day before yesterday I presented on OOP in Synergy/DE version 9. Here’s essentially what I said:

What is OO?

“OO” is the sound people are supposed to make when they behold your beautiful object-oriented code – but in many cases it comes out “OOPs” instead. In this presentation I hope to provide some insights on how to evoke the desired exclamation.

Object Orientation is both a design philosophy and a set of programming language features to support it. Languages that provide the latter are often called Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) languages. Object Orientation’s primary goal: to make the code describe the real-world objects involved in the application, and their interactions and relationships, thereby reducing the translation between business rules and computer instructions.

How does this apply to business applications?

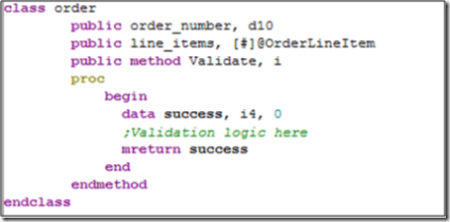

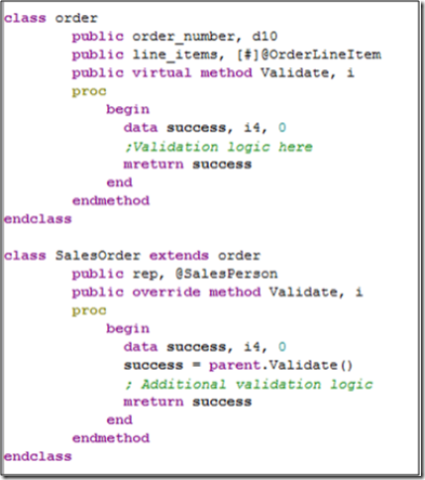

Well, you could begin to model your business processes in code. Given an order entry system, for instance, you might make “Order” a class that contains all the data related to an order and the methods to do what an order needs to do. A class defines a type of object. So, an Order will contain some general information about an order and a collection of line items, along with methods to retrieve, commit, and maybe validate that data.

You might then find that sales orders and purchase orders have a lot in common, but differ somewhat. So, you make both the SalesOrder and PurchaseOrder class “extend” the Order class, adding data and procedures that are unique to each, and possibly overriding some behaviors of the base Order class.

As you apply this principle to more areas of your application, you might start to see patterns emerge. A lot of what you do to store, retrieve, update, delete, and list orders also applies to other types of tables. You could then make the Order class extend some even more generic class that provides methods and data for manipulating any type of discrete data item. If you’re familiar with Design Patterns, you might want to follow the Model-View-Controller pattern and call this class a Model. Then you could create a View class which represents any type of user interface for the data, and extend that for specific ways of looking at certain types of data (input windows, lists, etc.). Finally, a Controller class could be used to orchestrate the overall behavior of an application, and extended to create specific types of applications.

“Whoa! You’re talking about a complete rewrite!” I hear you cry.

You’re right — that’s a bad idea. Any of you out there who have ever attempted it can testify that for any application that has taken many years to mature, a complete architectural overhaul is not in the cards. You simply cannot rewrite from scratch and have any product ready to ship before you go out of business. You need to incrementally incorporate newer methods and technologies in a way that allows you to continue to release your product on a regular basis. And you don’t want that pavement-to-dirt feeling when your user navigates between different parts of your application.

So, I expect that most of you will begin using objects without even really thinking about OOP. First, you’ll start consuming some of the supplied classes. The new dynamic Array class might prove handy, with which you can size an array at runtime without having to use the obtuse ^m syntax. You’ll be using classes and not even know it.

Or, quite likely, you’ll see the new try-catch-finally structured exception handling in Synergy 9 and say to yourself, “Self, you’ve been looking for something to replace that goto-by-any-other-name-still-stinks onerror statement for ages. Time to learn something new.” As soon as you catch your first exception, you’ll have an Exception object in your hot little hands. You’ll see how naturally you can access the information contained therein using the new object syntax. Maybe you’ll create your own derived class of exception in order to add your own custom information about an error encountered in your application. That might be your very first class definition.

Then you’ll start to discover more of the useful features of objects. For instance, scope and destructors. How many times have you wrestled with problems related to cleaning up resources when they’re no longer needed? The UI Toolkit provides the environment concept to release all resources that were allocated in an environment when that environment level is exited, which works fine for many cases. But in more complex applications you often find that you need to preserve some resources across environment-level bounds. So, you promote those to global, but then you have to remember to clean them up when you’re done. Wouldn’t it be nice if the resource would just get cleaned up automatically as soon as you lose all references to it? That’s what you can do with a class.

As you begin to think more in terms of objects, it will become more natural for you to create classes that model other aspects of your application. But don’t rush yourself. And don’t massively redesign, unless you’ve got a lot of extra time on your hands.

General principles

A class should reflect a single type of object. That means it’s a noun — some actor within your application. Without referring to existing code, try to describe, in natural language, how your application works from the user’s perspective. Whenever you encounter a noun, that’s a candidate for a class.

Methods are verbs that describe some action that a class of object can perform, on other objects or on itself (or intransitively). If the name of the method doesn’t involve a discrete action, then maybe it needs to be thought out differently.

Properties can be seen as adjectives that describe the object, or members that compose it. If your class has a property that you can’t think of in one of these ways, perhaps it shouldn’t be a property of this class.

A class should extend another class if it passes the “is a” test. A Bugatti is a car, so Bugatti extends the class of cars (does it ever – this baby can do 253 mph. Why from here to Los Angeles — of course, you couldn’t do 253 mph all the way to Los Angeles, because there’s always some jerk hogging the left lane at about 180). A Bugatti is not a chassis. A Bugatti contains a chassis, it isn’t derived from it. That distinction trips up class designers all the time. For instance, given the Model class we discussed earlier (from which an Order is derived), does it extend or contain a database table?

Often you can get away with inaccurate inheritance models for a while. But eventually, the practice of deriving classes from things that they logically contain causes conflicts, because you end up wanting to derive them from more than one ancestor class. Use the “is a” test to avoid that problem.

Signs you should have contained:

–You feel the need for multiple inheritance

–You add way too many methods

–You don’t override any virtual methods

Sign you should have inherited:

–You replicate all of the same methods and just forwards or duplicates them

What else to avoid

As Ken Lidster has said to me on many occasions, OO rewards a good design handsomely, but punishes a bad design to the end of your days. Lets discuss some common pitfalls.

In Execution in the Kingdom of Nouns, Steve Yegge describes how Java’s (and C#’s) insistence on requiring all functions to belong to a class causes programmers to manufacture many needless nouns in order to perform any activity. You don’t have to fall into that trap in Synergy/DE, because Synergy/DE provides stand-alone functions. So if your description of a process begins with a verb, just make it a function. Don’t give it an actor if it doesn’t need one.

Classes whose names include the words “manager”, “broker”, “locator”, or any other verbal noun, should be suspected. If the noun’s purpose in life is merely to perform some action, then that should be a function instead of a class.

What about singleton classes? Singleton classes are only instantiated once. Sometimes that means that they’re really just a set of global data and functions disguised as a class. Take, for instance, an Application object. Java and C# virtually require classes like this because otherwise you can’t get anything done. Because these languages require that you have a class to contain any function, you typically pick yourself up by your bootstraps by creating an Application object that has, at least, some sort of ”run” method. You don’t need that in Synergy/DE, unless it’s useful. Singleton classes can be useful for encapsulating related data and functions together, creating derivations of similar applications, and for avoiding global naming conflicts — but be careful not to let them become big, miscellaneous messes or just the equivalent of namespaces.

In OOP and the death of modularity, Chad Perrin notices a trend in object-oriented programming in which classes become coupled with one another, reducing modularity. Sometimes, by thinking in terms of objects rather than starting with processes, you can bundle too much functionality together into one class. Interfacing with such a complex class soon requires complex knowledge about how that class operates, creating unnecessary dependencies. By contrast, keeping the design simple and atomic requires less intimate knowledge and maximizes reusability.

Geek24 provides a series of humorous programming quips, including: ”The great thing about Object Oriented code is that it can make small, simple problems look like large, complex ones.”

Unfortunately, that often proves true. But you can avoid doing that, and make OOP work for you instead:

Avoid creating overly ornate inheritance hierarchies. Focus on the abstractions that you use in the business model, and ignore the rest. In real life, we always ignore certain layers of abstraction. It’s useful, for instance, to talk about an overnight envelope as a type of shipment, but we rarely need to state the fact that all shipments are types of molecular collections. That’s not the level on which we operate. Likewise within an object hierarchy, don’t bother including ancestor classes that no one will ever need. Make use of inheritance where it makes sense.

Rule of thumb: simplify. If adding a class simplifies the code and makes it easier to understand and manipulate, that’s a good design. Oooo. If it complicates the code and adds unnecessary layers and dependencies, you were better not to use objects at all. OOPS! The beauty of Synergy/DE is that it lets you decide.